This past week has been spent working on optimizing the height map to 3D model algorithm and finishing upgrades to the manipulator. All that’s left to do is characterize the limits of our system and gather data that compares our scans to a traditional 3D scanner’s.

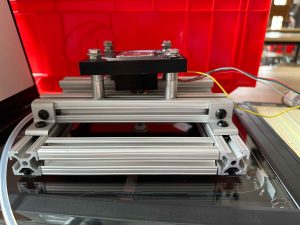

Theo finished the linear bearings upgrade to the manipulator and has made a new design for the electronics housing.

Yon worked on printing some parts including the test object, and writing the object comparison algorithm.

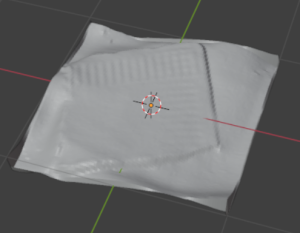

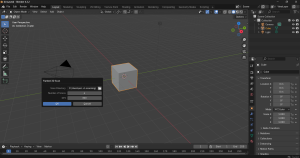

Sophia started testing and bug-fixing code for the automatic import of the height map into an object in Blender. So far it creates the plane, but it’s having trouble to find the correct file path for the height map. It should be able to be fixed before the final demo, but worst case scenario it takes maybe a minute to manually create the plane and add the height map to create the object in Blender.

Unit tests for the manipulator included measuring out precise rotations and making sure the manipulator could be placed on and rotate objects of different heights and sizes. We’ll continue to test this through our system test.

There are two main areas of the image processing system that need to be tested: image alignment and model creation. Image alignment can be easily tested by running several different shaped objects through the system and ensuring the resulting bounding box represents aligned images. The model creation part is a little harder to test, and is the reason we Yon has been working on the test object and model similarity score algorithm, which will general a similarity score between our scan and the ground truth, along with a quality score comparing our scan with the benchmark scan of the same object. We can only really test this on an object for which a ground truth exists, so this won’t exactly be a ‘unit test’. We will also run scans on a variety of different objects and perform a visual inspections on them.

Unit tests for the software include running the files individually to make sure they completely worked before adding another file to the system pipeline. Ex. we ran the dotNet C file (which runs the scanner) first many times, then ran the Main.py file which would include running the dotNet file, then running the align file repeatedly to make sure it works, then added in the align file to Main.py and ran it many times to make sure it works, etc. So it was an iterative process of running individual files, then adding them to the system after they’ve shown they worked individually, then running the system to iron out integration.

Our overall system test consists of:

- Place object on scanner

- Place manipulator on top of object

- Plug in manipulator and scanner to user’s computer (both USB)

- Run project script. The system alternates between scans and rotations until the object has been rotated around to its starting position.

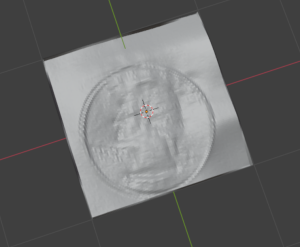

- The image processing automatically derives the normal map of the object and then generates a height map.

- The height map is imported to Blender for the user to inspect and interact with.

The only work from the user is during the setup. After starting the script, it only takes a minute or two (depending on the DPI of the scan, a modifiable parameter) for the object to be viewable in Blender.