The only remaining work to be done is to add the audio component, which simply involves connecting the earbuds via bluetooth and then calling some Python library like “subprocess” to connect the earbuds, and then “pygame” to play an audio file. We have the logic for when each audio file should be played already. There is also the compass component, which should also be quick.

The final design for the chest mount has been completed. The final revision adds a front plate, neoprene padding, and uses black and smoke grey acrylic.

Unit tests:

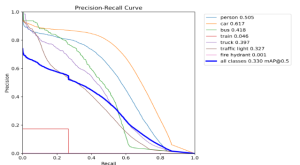

YOLO model (90 ms inference)

The performance was good enough and the speed was fast enough to not have to make any design changes. We also observe that in practice, the model does well enough to identify obstacles in the field of view:

For the initial verson of the navigation, we provided feedback to the user based on how close a detected obstacle was to the camera. However, in common scenarios where a person is just overtaking the user, this logic is insufficient, such as in the example image below during our testing at a crosswalk on campus:

In order to address this, we needed to update our navigation submodule slightly, allowing for a slightly more nuanced logic with regards to whether or not to alert the user to specific obstacles. We will need to include in our system wide testing as well, to make sure that the navigation behaves as anticipated as part of a larger system.

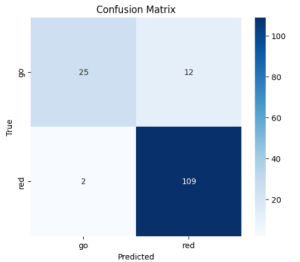

ResNet model (30 ms inference)

Again, the performance was good enough and the speed was fast enough to not have to change the model or size.

For the overall system test, no numbers have been collected as of yet. However, we plan to run it as follows:

First, we wear the device (without being blindfolded). Next, the we wait at a crosswalk, ensuring that the “Walk Sign” cue is only played when there is a valid walk signal. Once the light displays “WALK”, we begin crossing the road. We will ensure that the device functions properly for both a clear crossing with no deviation, a crossing with objects in the path, and a crossing where we deviate from the path. At the end of the cross road, we also ensure that it resets back to the original Walk Sign Detection model (our idle state).