Monday’s ethics lecture gave us a lot of new perspectives and it was interesting to sit in and listen. After that, we continued work in our own areas. As Gordon continued to set up the KRIA and Jimmy continued to work through the camera, we were thinking through the feedback we received last week about the overlapped functionality between camera and KRIA. Jimmy has done great with setting up the CV model with our OAK-D camera, and even got the chance to run a Kalman filter on it. Josiah has been doing great with the robot, getting the chassis built. Gordon was working next to Jimmy during this, and it sparked a conversation about what would be left for the KRIA to do if the camera is capable of running the Kalman filter as well.

Originally, we had planned the KRIA to potentially house the CV, run the Kalman filter + trajectory calculation models, and utilize the on board FPGA for hardware acceleration, while the camera would be sending in video frames or ball position. We hadn’t really dived into the exact divide of labor between camera and KRIA, because we weren’t sure of the exact capabilities of both systems. We knew generally what they could do, but didn’t know how well each component would work in a technical sense, like with what accuracy can the model of the camera detect the ball, latency of sending data between systems, or how complex the Kalman filter code is and the feasibility of writing HLS to utilize the hardware acceleration. Thus we had originally proceeded knowing that there were potentially going to be questions about the camera and KRIA interface, and potentially an overlap in functionality.

We didn’t expect the camera to be so powerful, capable of not only doing depth sensing but also running the CV and the Kalman filters. At this point with the camera doing so much, all the KRIA can offer is the on board FPGA to accelerate any calculations before sending off the landing coordinates to the robot. Even that would require writing our own Kalman filter model in C in order to use the Vitis HLS for hardware acceleration, which is a very challenging task (difficulty of doing this confirmed by Varun, FPGA TA guru). Yes it could also be nice to utilize the SoC of the KRIA to run CV models instead of a laptop, but something like a Raspberry Pi could get the same job done with way less technical difficulties and setup overhead. The difficulties of the KRIA and what exactly is “difficult to set up” are elaborated upon more in Gordon’s solo status report.

Because of all this, more discussions about the role of the KRIA were held, and Gordon met with Varun the FPGA guru to get his input as well. Overall, it was decided that next steps could follow this plan:

- Research into if a raspberry pi will be able to handle everything necessary, keeping the KRIA as a backup plan. Consult table below for pros and cons of KRIA vs raspberry pi.

- Benchmark how long the CV+trajectory calculation would take running on a Raspberry Pi, hopefully interface with robot and determine if we can get away with just using the Pi

- In parallel with #2, if Kalman filter is just in python right now, try changing it to be in C

- Two reasons why. First, C programs run faster than python programs, so with latency being even more crucial now this could be worthwhile.

- Second reason, in case we need to fall back to KRIA, to use HLS we need a C file for what we want to be converted to RTL for hardware acceleration

- Although it’s possible that people have wrote similar Kalman filters for HLS already, research online on availability and feasibility of other people’s code

| Pros | Cons | |

| KRIA | Potentially the fastest overall computation, although unsure exactly by how much

More powerful SoC, potentially able to run programs faster than raspberry pi Already have the board |

Difficult to set up and get running, would require a lot of research into how it interfaces

Would take a lot more work to have Kalman working on HLS Potential speedup maybe not worth the massive knowledge and setup overhead |

| Raspberry Pi | Significantly easier to use and setup

Effectively the same function as KRIA without FPGA |

Potentially more latency

|

Admittedly, timeline wise this is later on in the semester than we hoped to be having these design changes, but given our workloads and other events happening during the past month and the fact that we already have a lot done, we are confident that we will be able to pull through with these changes. In fact, changing to the Raspberry Pi eliminates the complicated KRIA work and makes it more feasible to complete this aspect of the project. We will look into where to get the Raspberry Pi ASAP, and begin work to catch up.

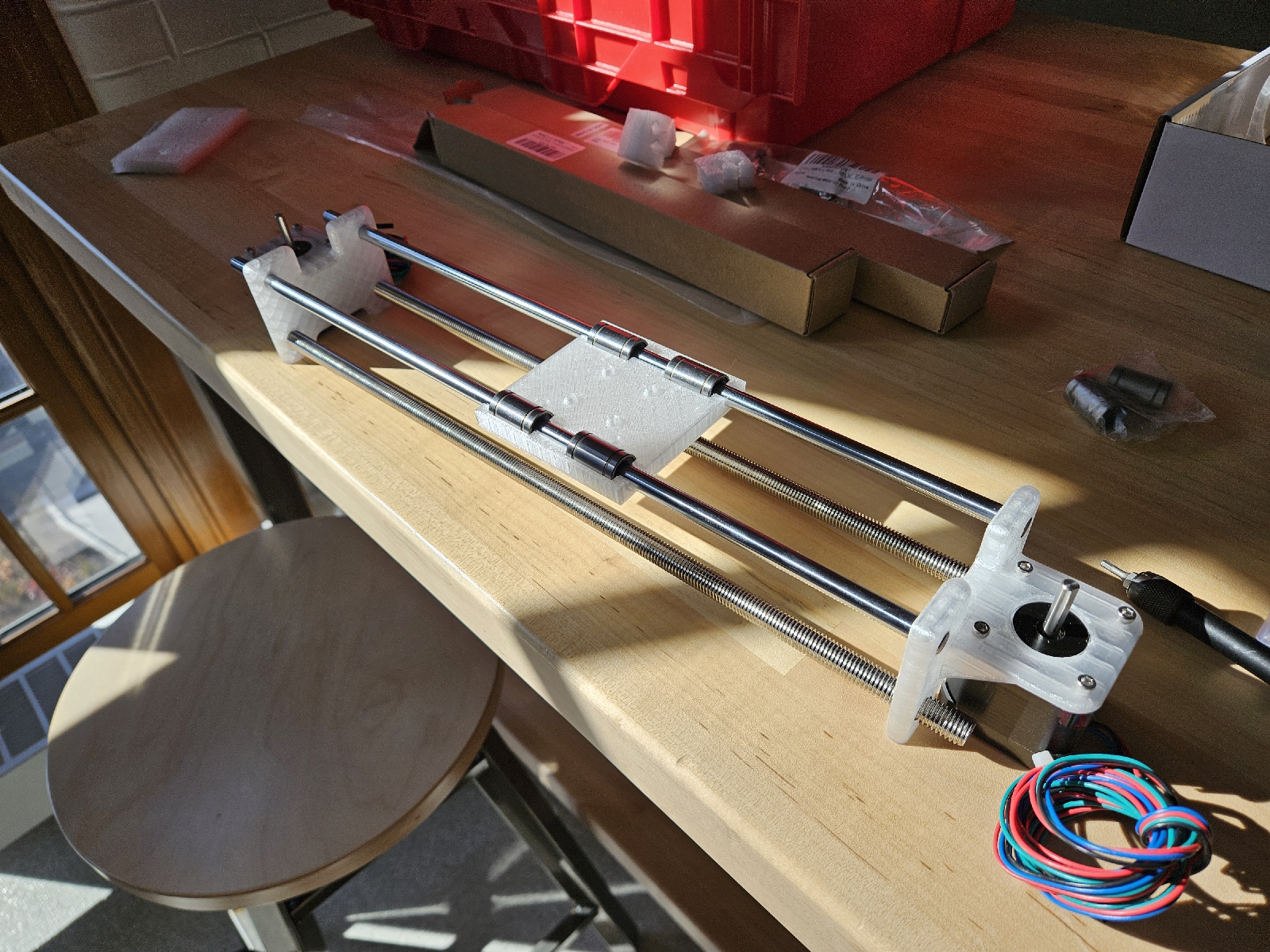

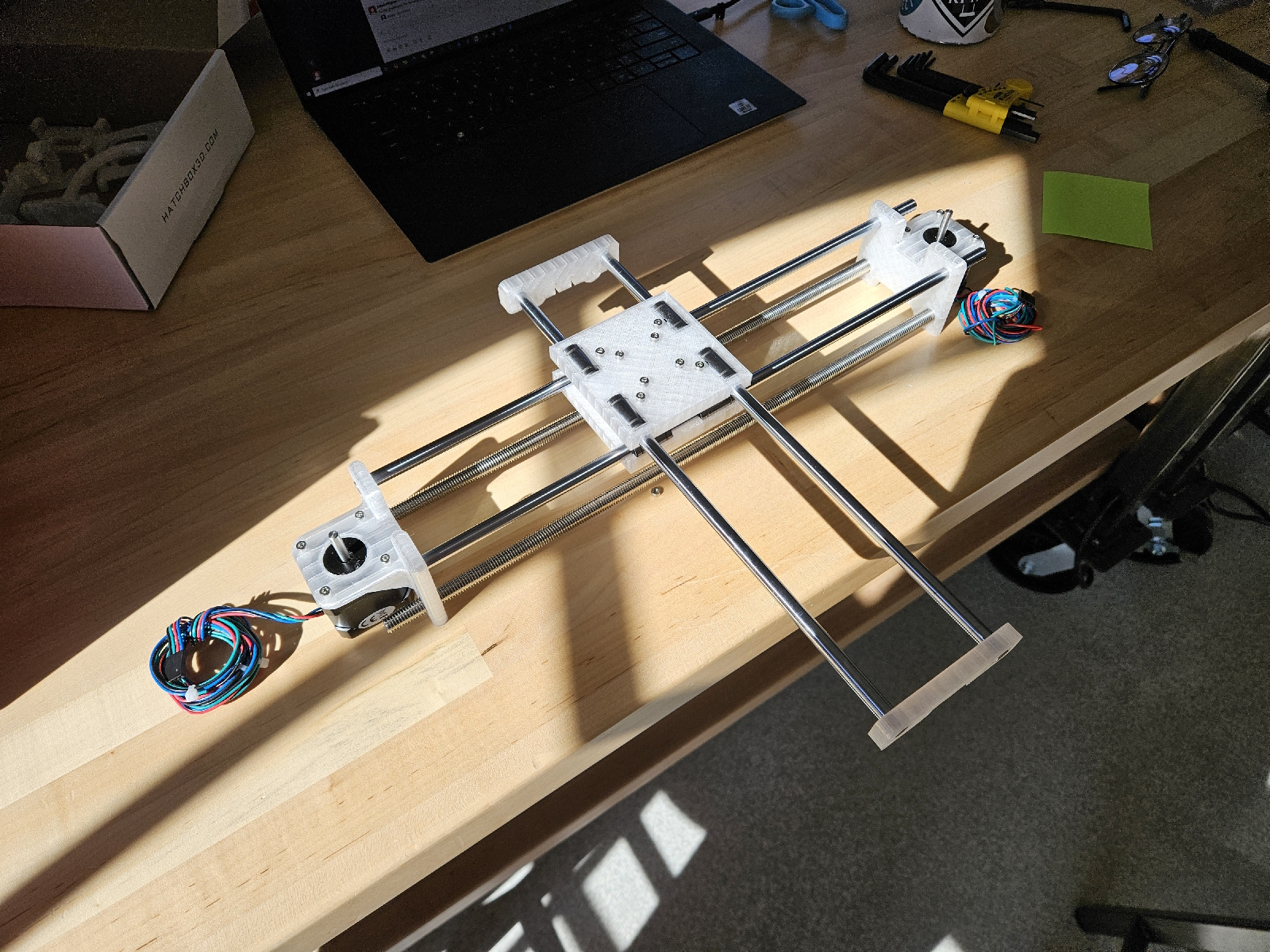

Regarding the robot, assembly is well underway, and is looking to be completed this next week. Check out the photos for progress!

For the camera, a lot of work was done in integrating the detection and tracking pipelines, and now we are able to fully detect and track the coordinates of a moving ball, with good accuracy thanks to the addition of background subtraction filter. A big risk the remains is the kalman filter, with details being described in Jimmy’s status report.